BY MICHAEL FARMER MICHAEL FARMER REPORT ARCHIVES

Creative advertising agencies are, by their nature, cheerful organizations filled with frustrated and insecure individuals who weave good stories. Annual industry surveys of agencies are the last place to look for industry truth -- collective pessimism, which is what industry surveys reveal (i.e., "Ad industry morale drops 36% from 2015") is only one point of view, and it is outweighed by the colossal self-confidence exuded by newly-appointed senior agency executives in interviews with the trade press (i.e., "We are now completely focused on elevating the quality, impact and profile of our work. It is our very reason for being and nothing could be more important. My confidence could not be higher."). These same agency executives may acknowledge privately that their industry is in terrible straits, but since they need to believe in themselves and in their ability to lead their agencies back to success, they put on a good show.

What, then, can we say about the prospects for creative advertising agencies in the year ahead? Will senior executives' collective commitment overcome the industry's negative trends? Will senior executives demonstrate that they are championship swimmers who can conquer the undertow? Or, instead, will they be swept out to sea, victims of overconfidence and weak change programs?

Unfortunately, I cast my vote for the undertow. I believe that Madison Avenue's manslaughter will only worsen. Senior executive actions, as they have been defined, are inadequate, and creative ad agencies will be in a worse position at the end of 2017 than they are in today.

Let's define the undertow. Agency economics are deteriorating and have been steadily deteriorating for several decades. Scopes of Work (SOWs) have been relentlessly growing, fueled by client-led digital and social media experimentation, while procurement-led fees have simultaneously declined. This leads to a chronic erosion in the price that creative agencies are paid (fees divided by workloads). However, since agency SOW workloads are not measured in any meaningful way, the decline in price is not a familiar metric for senior agency executives. In their minds, there's no such thing as a price that agencies are paid for the work they do. The only price they're aware of is the hourly rate of their people. The fallacy in this, of course, is that clients are actually buying agency work, not agency hours, in the hope of growing their brands.

This is a problem unique to the advertising industry. Senior agency executives do not know of or track or fix their pricing problems. Pricing is not on their radar scope. Yet, ironically, industry pricing is the No. 1 problem facing senior creative agency executives today.

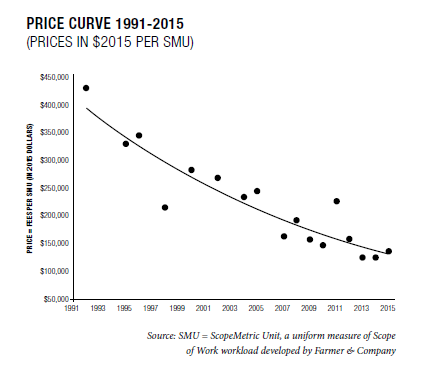

I've been tracking the price of agency scopes of work since 1992, when my firm developed a way to quantify the SOW workloads of our clients, normalizing the variety of SOW deliverables into a uniform measure of work, the ScopeMetric® Unit (SMU) -- a unit of work about the same size as a typical TV spot.

If the price received by my agency clients was indexed at 100 in 1992 (with inflation removed), it declined to 56 by 2004 and then to 35 by 2015.

This pricing problem has created Madison Avenue's manslaughter.

Declining prices have to be matched by declining costs, at least if profits are at all important. This means reduced salaries and limited bonuses for agency people. As it stands now, agencies severely underpay their people relative to other service providers, like Google, Facebook and management consulting firms. Check it out on Glassdoor.com, where salaries are published. On top of this, the underpaid creatives have had to double the amount of creative work they develop each year. Declining prices have stretched creative agency resources.

Falling prices, and the associated consequences, have brought about a decline in creative quality if we measure quality by the willingness of advertisers to keep agencies on their rosters. Alas; the length of agency relationships has fallen to only 2-3 years, significantly down from the 15+ years during the media commission days.

The undertow is pretty strong, and it is not being dealt with. There are few, if any, executive programs designed to put a floor under declining prices.

What, instead, are senior agency executives working on or talking about? Improved project management. Better data analysis. Improved new business pitching. Improved creativity and the winning of awards. The strengthening of digital and social services. Hiring new talent. Working in holding company relationships. Downsizing when profit margins are at risk.

These are not initiatives that have a chance of turning around agency performance. Let's not ignore the fact that clients single-mindedly focus on improving shareholder value, which only the management consulting firms take to heart as their raison d'etre. The consulting firms who now have creative capabilities pose a real threat to today's creative ad agencies. Consultants will mobilize their consulting and analytical expertise with their new creative capabilities to generate improved marketing results for clients, while ad agencies, remembering what made them successful in the past, will be stuck in a rut, thinking about how to become more creative.

Agencies have not yet reached a destructive tipping point. They can still operate and generate profits for the next few years, and newly appointed senior executives can trot out the tried-and-true agency slogans that convince themselves, if not others, that they have genuine turnaround plans.

But they are not really accomplished swimmers for the treacherous seas of 2017, and my bet is that the undertow will take down a number of them in the year ahead.